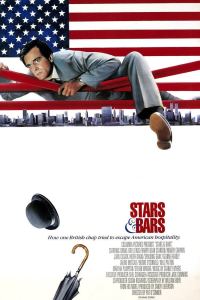

This novel, Boyd’s third, is set contemporarily in the 1980s first in New York, and then in the Deep South. The main protagonist (if you can call him one) is Henderson Dore, a British art appraiser working for a fine art consignment house. He’s sent on an assignment to visit an elderly millionaire, Loomis Gage, somewhere in the Deep South and conduct a valuation of this man’s 18th century Dutch paintings, make an offer, and work with the best auction houses to have them sold.

This novel, Boyd’s third, is set contemporarily in the 1980s first in New York, and then in the Deep South. The main protagonist (if you can call him one) is Henderson Dore, a British art appraiser working for a fine art consignment house. He’s sent on an assignment to visit an elderly millionaire, Loomis Gage, somewhere in the Deep South and conduct a valuation of this man’s 18th century Dutch paintings, make an offer, and work with the best auction houses to have them sold.

The story is a farcical tragicomedy, and since you’re unlikely to care for any of the characters, it could also reasonably be called an ‘uproarious’ comedy. In other words, expect endless cringing and lots of terrible decision making.

Dore is a fairly terrible person, thinking primarily (if only) of his own self-interests. He’s nurturing an affair, and first looks at the trip as an opportunity to get away with his mistress. Not so. The daughter of his ex wife (not his own), who he is hoping to remarry, imposes herself in the first of an endless series of miscarried plans and unnecessary complications.

They head to Luxora Beach, a fictional, tiny, landlocked town in central Georgia. There is no beachfront to speak of, and instead the town is fecund with overgrowth and proudly displays the Stars and Bars (aka the ‘Southern Cross’ or Confederate Flag) in equal ratio to the bright neon signs boasting a red bow and blue rosette (PBR).

Early on, Henderson’s character is described as “[suffering] from all the siblings of shyness: the feeble air of confidence, the formulaic self-possession, a conditioned wariness of emotional display, a distrust of spontaneity, a dread fear of attracting attention, an almost irrepressible urge to conform…” which primes us well for the endless humiliations, missteps, howling blunders and miscalculations to come.

People laugh ‘unattractively’; the family imitates him and he ‘charitably’ ignores them. He is demonstrably the story’s narrative voice (‘charitably’ also giving himself endless passes), but an unreliable narrator in the sense he always feels he’s always on the right side of propriety. He isn’t. The clichés are clearly overdone, but that makes the conflicts all the more ghastly, so if you like dramatic irony… get the popcorn.

As a British man in the Deep South, he is of course met with impersonators. It was never going to be any other way. “You know, I’m trying but I just can’t make sense out of what you say. You know, it just sorta sounds like “Mn, aw, tks, ee, cd, ah, euh” to me.”

They imitate him, and at first he ignores them. Shortly, he decides they will only understand him if he communicates by mimicking their speech, and oddly? It works. He pinches his nose and… “Well shucks, I reckon I jist plum done gone and forgit to ask you to do me a service, like, goshdarn it.”

It’s quite funny at points, but there are so many deeply excruciating episodes in this book, I can give it no more than three stars.

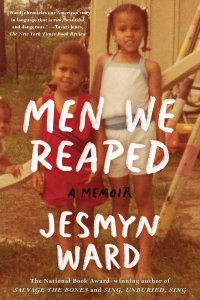

In Men We Reaped, Jesmyn Ward tells a personal story of five young black men in her life who died over the space of four years, interwoven with her own story. One told chronologically, the other in reverse, ending at the heart of the story.

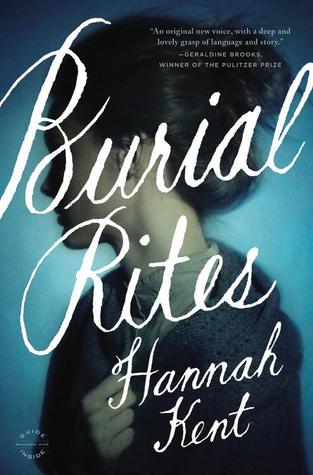

In Men We Reaped, Jesmyn Ward tells a personal story of five young black men in her life who died over the space of four years, interwoven with her own story. One told chronologically, the other in reverse, ending at the heart of the story. Burial Rites is the story, told through many narrative voices, of the final year in the life of the last woman to be publicly executed in Iceland, Agnes Magnúsdóttir. The setting is Northern Iceland, 1829, and Agnes is sent to a croft dwelling to live with a family she’s never met as she awaits her execution date. In the early 19th century, Iceland had no prisons, hence Agnes’ assignment to this farm. Iceland was also still under Dutch rule and you can feel the distance and isolation intensified by these small judicial formalities.

Burial Rites is the story, told through many narrative voices, of the final year in the life of the last woman to be publicly executed in Iceland, Agnes Magnúsdóttir. The setting is Northern Iceland, 1829, and Agnes is sent to a croft dwelling to live with a family she’s never met as she awaits her execution date. In the early 19th century, Iceland had no prisons, hence Agnes’ assignment to this farm. Iceland was also still under Dutch rule and you can feel the distance and isolation intensified by these small judicial formalities.

Tara Westover grew up off-the-grid. Her survivalist family worked in the scrapping yard, eschewed education and government, and loosely subscribed to Mormon fundamentalism. Her father, something of a prophet within his nuclear family, believed in the Illuminati, was certain that Y2K would be the end of days, and brainwashed his family into believing that the government would show up any day to raid the farm for not sending the children to school. Her mother was a reluctant midwife who believed in muscle testing and herbal tinctures, hired an entourage to work on oils and salves, and used these in lieu of medicine. In this memoir, there are countless, hideous scenes of horrific accidents. One thing must be said: they truly believe in what they preach. The ultimate tests come when they are physically mutilated and near death, but still rebuff any offers to go to the hospital for medical attention. They endure car accidents; oil tanks exploding in their face; near-death incidents as they hang off the side of unbroken horses, caught up in stirrups; 12 foot falls onto rebar; unspeakable motorcycle injuries; brutal physical and psychological abuse … and despite this, the memoir doesn’t feel voyeuristic or even judgmental.

Tara Westover grew up off-the-grid. Her survivalist family worked in the scrapping yard, eschewed education and government, and loosely subscribed to Mormon fundamentalism. Her father, something of a prophet within his nuclear family, believed in the Illuminati, was certain that Y2K would be the end of days, and brainwashed his family into believing that the government would show up any day to raid the farm for not sending the children to school. Her mother was a reluctant midwife who believed in muscle testing and herbal tinctures, hired an entourage to work on oils and salves, and used these in lieu of medicine. In this memoir, there are countless, hideous scenes of horrific accidents. One thing must be said: they truly believe in what they preach. The ultimate tests come when they are physically mutilated and near death, but still rebuff any offers to go to the hospital for medical attention. They endure car accidents; oil tanks exploding in their face; near-death incidents as they hang off the side of unbroken horses, caught up in stirrups; 12 foot falls onto rebar; unspeakable motorcycle injuries; brutal physical and psychological abuse … and despite this, the memoir doesn’t feel voyeuristic or even judgmental.

This short volume is both accessible and short enough for anyone to read in a single setting. Mary Beard developed this piece from two lectures starting with examples from Greco-Roman mythology, like the earliest example in literature of a woman being told to shut up (Telemachus to his mother Penelope in the Odyssey), to more recent examples of how women are silenced and kept out of power. She writes right up to the Kavanaugh confirmation hearing, to Elizabeth Warren’s silencing on the Senate floor, Teresa May’s Prime Ministership (the lectures already feel dated in some regards), and the unrepeatable things her opponents say to her on Twitter.

This short volume is both accessible and short enough for anyone to read in a single setting. Mary Beard developed this piece from two lectures starting with examples from Greco-Roman mythology, like the earliest example in literature of a woman being told to shut up (Telemachus to his mother Penelope in the Odyssey), to more recent examples of how women are silenced and kept out of power. She writes right up to the Kavanaugh confirmation hearing, to Elizabeth Warren’s silencing on the Senate floor, Teresa May’s Prime Ministership (the lectures already feel dated in some regards), and the unrepeatable things her opponents say to her on Twitter. This book would be most relevant to women who are fortunate enough to have choices, especially how much and when and where they want to work. Sheryl Sandberg makes a lot of space for what people might look for out of life, but quickly makes it clear that this book speaks particularly to women who place a high value on career success. There are many situations that most (or every) women will face in the workplace, within their communities, and at home. By and large, the core of this work is about developing yourself within the bounds of your career, including your own guiding approach to personal sacrifice.

This book would be most relevant to women who are fortunate enough to have choices, especially how much and when and where they want to work. Sheryl Sandberg makes a lot of space for what people might look for out of life, but quickly makes it clear that this book speaks particularly to women who place a high value on career success. There are many situations that most (or every) women will face in the workplace, within their communities, and at home. By and large, the core of this work is about developing yourself within the bounds of your career, including your own guiding approach to personal sacrifice.